Is it not so, that from its conception, Christianity has always, to some degree, been wrapped up and consumed by Empire? There is a dark and ominous foreshadowing in the temptation of Christ, where Satan offers up the kingdoms of the world, in all their glory. We realize, of course, that we have submitted ourselves to the demonic, that now, in hindsight, Christ left the desert with a golden crown on his head, and descended upon his glorious, gilded throne, rather than dying there on the hill in golgotha.

Perhaps this is what Martin Scorsese really intends with his film, “The Last Temptation of Christ”, where Christ (Willem Dafoe) submits to the temptation to wield God’s power and remove himself from the cross. He goes on to live a normal life, marrying Mary Magdalene having children, etc. Perhaps Scorsese gets at a horrible reality of our Christian condition today, that our Christianity looks more and more like Christ submitted to Satan’s temptations, that he had given into the conditions sanctioned by the ruling elite, and surrendered into the bourgeoisie, leaving our world relatively unchanged and forever steeped in slavery.

One does not have to take up the Scepter to live in the King’s Court. All that is necessary is that we don our Jester’s cap and juggle for their entertainment. We do this everyday by playing by the rules, surrendering to the language of power, perpetuating racism, sexism, and classism. We should, as Anabaptists, reevaluate and redefine nonviolent pacifism. It isn’t enough to be simply passive, there must be something more, something that challenges the system as much as it condemns it. Modern pacifism is properly ideological, it allows a system of oppression to persist unperturbed.

But still, there is hope. Towards the end of Scorsese’s film, Jesus finds Saint Paul preaching the resurrected Christ, and when he confronts him and explains to him that he is indeed the son of Mary and Joseph, saved by the grace of God from the cross, Paul reply is simply, (paraphrased) “No, you aren’t.”

This same hope has been echoed throughout all of Christian history. Where there has been the bourgeoisie Jesus, who submitted to the temptation of Satan, and went onto live a life of power, there has always been the St. Paul, echoing Scorsese’s Paul, boldly proclaiming in the face of evil, “No, you aren’t [Jesus]”.

Perhaps one of the most notable theologians who stared into the face of King Jesus (as opposed to Christ, the king) without hesitation was Thomas Aquinas, who, 900 years after St. Augustine conceded to the empire that a Christian could serve as a soldier honorably, responded to such perverse nonsense with his Just War Theory. The Just War theory is undoubtedly one of the most misunderstood doctrines in Christian History. It is of course a declaration that openly opposes Augustine’s submission to the violence of the state.

Aquinas constructed the doctrine in such a way that none of its conditions can ever possibly be met. From the get go, the first proclamation is totally ridiculous. “Just war must always be waged by a properly instituted authority such as the state”. Properly instituted would imply that the state had a legitimate means of existence, when of course, we realize, a state has never existed in such a way. A state’s existence always first relies upon a domination and oppression of another. Is the violence of the Old Testament not enough to make us realize this? That in order to establish a state, some legal precedent must always be broken, someone must always be left out, the establishment of a state is always objectively violent. There is simply NO state that has been “properly” instituted.

Aquinas intended for the Just War Theory to be a call to pacifism. Where war was waged, the Christian would always inevitably run up against a violation of one of the conditions of justification, and thus, would actively disengage from the state’s imperialist, demonic, violent exploits. Aquinas’ theory succeeds in effectively removing the temptation of the Christian to participate in State Violence (a violence that always benefits the elite and is leveraged on the backs of the oppressed), but it failed in not implying any type of action or alternative. Where state violence is allowed to persist, where we are inactive, we ultimately BECOME the passive oppressor, we become a passive instrument of the state, even if we do not intend it.

The 2014 Shenandoah Confession, written by a group of intercollegiate Anabaptists, is an ironic reversal to Aquinas’ Just War Theory, where suddenly, the very inaction intrinsic to the confession, becomes the only (politically) active resistance to the oppression in our world today. Its demands are impossible, and our confrontation with that fact suddenly brings on the revelation of how consumed we are, how entangled we’ve become, with state violence. The only reason the demands are an impossibility is because we simply do not have the language available to us to be able to achieve them. Language is for the capitalists, the globalists, the imperialists and the priests. Where there are no words to express peace, there is no peace, where there are no words to expressive inclusion, there is no inclusion, where there are no words to express love, there is no love.

Of course, we should be cautious here. To say that something isn’t present is not to say it does not exist. Where something cannot be said, it must be shown. Would it be better for us if we simply acknowledged the love does not exist, but rather, ex-ists, as something transcendental, incapable of expression through language. Should we not preserve the beauty of virtue by allowing it to remain silent, and instead, simply moving (in the most literal sense) ever towards it, with our every action, our every motion, our every step.

This is what the Shenandoah Confession commands, not that we accept these set of doctrine as a “belief”, but rather, that we simply practice them, without ever having to speak them at all. This is, undoubtedly, why it is labelled as a “confession”, rather than simply a manifesto. In following the tradition of the Schleitheim Confession of 1514, the students are actively acknowledging the inactivity that has for too long dominated the discourse of Anabaptist Christians. Enough talking, we confess, we have been too still. Now, let’s begin to move against the language of power by keeping our mouths shut and our bodies in motion.

On January 6, 1957, Elvis Presley made his third appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show. The censors decided that it would be best if they shot Elvis from the waste up, due to the perpetual and continuous motion of his pelvis. They were undoubtedly uncomfortable with the sexual connotation of Elvis’ dance moves, yet, incidentally, this tells us something about the art of dance, it tells us that dance has power, that it can shock our very sensibilities, so much so to the point that we have to turn away or black it out. It “says” something to us, without having to use words, and thus, it doesn’t domesticate the subject matter, it doesn’t make any concession to political correctness, it doesn’t “soften the blow” as words do, it is overt, intrusive, loud, and untamable.

Doesn’t this explain why, in middle schools all across the country, there are kids awkwardly slouched against the walls during their class dance. Or why, all throughout history, certain ballets and musicals have been banned from public consumption? Dancing is an uncomfortable exercise, it is awkward, frightening, it violates our personal space, it violates language itself.

So, in the same way, the Shenandoah Confession should be a confession that insists that we no longer stand still, that we get on the floor and “dance” with the state, that we interrupt the waltz (Which means to cover over the decadence of a society with something beautiful) with the ridiculous romp of rock and roll (which outwardly admits its a misfit on the fringes of a system). That we no longer stand by and accept the “end of history”, that we take a faithful step towards the apocalypse.

In Mark 6, Jesus stares into Pilates eyes and does not mutter a single answer to any of his questions. This is what the Shenandoah Confession should remind us of, that we have spoken too much, that the time has come to cut out our tongues, stare boldly into the face of power, and move towards our cross.

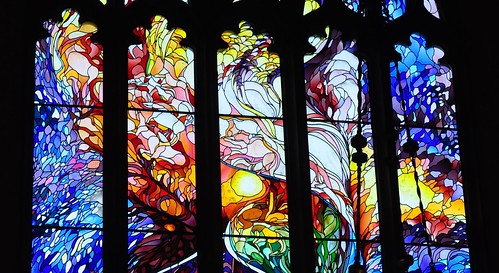

Photo by Tim Nafziger