Crossposted from As of Yet Untitled.

Tottenham High Road by Nicobobinus Some Rights Reserved

Tottenham High Road by Nicobobinus Some Rights Reserved

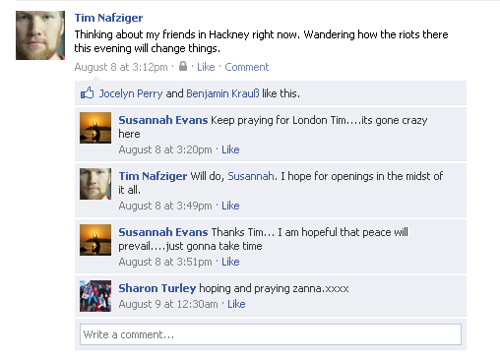

Last week, riots and looting moved through neighborhoods in London that I know well. The broken windows, fires and shouts of “I want a satnav*” were juxtaposed with a familiar map that I bicycled through to work for nearly two years. I found myself turning to Facebook to reach out to friends in those neighborhoods and processing my thoughts through comments on my favorite blog.

As I’ve reflected back on the last week, I notice that a more comment-and Facebook- focused response is a new one for me. Four years ago, immediately after I heard about the Virginia Tech shootings, I found myself alone with my laptop on a train ride to Chicago and wrote this piece as a way of processing my thoughts and frustrations at gun culture in the United States. As I saw reports of riots in Hackney and Tottenham, I felt a similar surge of emotion, but I found myself responding in fragments rather than a longer piece.

Much of the coordinated looting in London has been organized through a similarly fragmentary medium: that of BlackBerry Messenger (BBM), a private instant messaging service. I first became familiar with BBM through their omnipresent ads of smiling laughing 20-something socialites on the Chicago trains last year. It seems teenagers in London have found a different use for the service as they coordinate their raids on stores with particularly appealing consumer items. According to a friend of mine, some of them are as young as 11 or 12. These are kids who have grown up with texting and may never have known life without it.

And there’s the rub. As social scientist Clay Shirky points out, the use of new technology becomes truly disruptive (and innovative) when a generation grows up taking it for granted. He makes the connection with printing press, and particularly Aldus Manutius who essentially invented the paperback book:

The lesson from Manutius’s life is that the future belongs to those who take the present for granted. One of the reasons many of the stories in this book seem to be populated with young people is that those of us born before 1980 remember a time before any tools supported group communication well. For us, no matter how deeply we immerse ourselves in new kinds of technology, it will always have a certain provisional quality … When a real once-in-a-lifetime change comes along, we are at risk of regarding it as a fad. (more of this quote here:)

Here’s where the early Anabaptists come in. Shirky points out that the huge disruption of the protestant reformation came about through a generation who took printed books and pamphlets for granted. The Anabaptists were the most radical wing of that movement. They were also quite young and they understood how to use books and pamphlets in highly disruptive ways precisely because they had grown up taking them for granted. Hans Hut, for example, was a bookseller. David Joris was a writer of popular hymns, whose distribution as sheet music would have been vastly expedited by the printing press. Most Anabaptist leaders knew how to use a good pamphlet to radicalize their community. Even those who weren’t literate probably knew someone in their community who could tell them about the latest broadsheet, or even read it to them. Ideas could multiply like rabbits and travel at the speed of many horse.

So too are the rioters in London, the hacktivists of Anonymous and the youth of Syria, Egypt and Tunisia. They are innovating most radically with tools that have been around for a generation now. They are learning how to organize themselves rapidly and effectively using tools like Facebook, Twitter and BBM.

While there are plenty of problems that come with the more fragmented and instantaneous nature of texts today, let me offer a small window into some of the benefits I’ve experienced personally. I’ve noticed over the last few days, the fragmented approach is more relational and allows for more feedback and processing of a complex situation. On Facebook I was able to share thoughts with my circle of friends rather and hear their thoughts and feedback in return. More publicly, I noticed that 31 fellow readers “liked” my comment on BoingBoing. Specifically, it seems like people resonate with the connection I made between the instant gratification of consumerism and the impulsive grabbing of stuff by those who have no hope of attaining it through legal means.

So what can we learn? I’m not sure it makes sense to rage against these sea changes in our world any more than it did to rage against the printing press 500 years ago. These changes will clearly continue to disrupt our societies in both good and bad ways. They will be brought about in ways that we like and ways that we don’t. Let’s be on watch for those, who like the early Anabaptists, bring renewal to our world from unexpected places.

I see some similar dynamics playing out with PinkMenno and MCUSA.

Derek,

Interesting connection. The Pink Menno folks definitely made extensive use of texting to communicate up to the minute information to participants.

We should remember the non-aggression principle. I think it should be very important to embrace as Mennonites.

It took me a while to get to your point, but I see where you are going with this…the use of communication technology, hereto wit unavailable to the masses in the generation before, causes a certain disharmony in the status quo. The earliest Anabaptists ‘rocked’ their newfangled printing press. Today, other loose confederations, such as Anonymous, are embarking on ‘shaking up’ the status quo by using technology in ways most of us of the previous generation must confess a certain illiteracy.

Marlene,

Yes, that’s a good summary of my thesis. I think there’s a significant generation dynamic and work and I see it even more in younger generations than myself (I’m 30). I remember when email became widely used. Teenagers today don’t remember a world before texting.