On March 10, I visited my uncle Dennis Maust in his studio in northern Lancaster, Pa. It was a beautiful sunny day and the windows of his studio look out across rolling farmland to the hills of the northern border of the county. While he worked on his latest pieces, I asked him some questions about his work as a ceramics artist. But first I had a read through his essay “Living the Patchwork” in the latest issue of The Studio Potter for some background. This interview draws on themes from that piece. Dennis’s next show is in Lancaster for the month of July at Laporte Jewelers on Harrisburg Pike in Lancaster (across from F&M University). It is opening July 6th.

Found somewhere near Father Abrahams birthplace (unexploded), 2004. Photo by Dennis Maust

Tim: In the article in Studio Potter you talk about the period where you were building “protest-oriented pieces.” Can you say more about this?

Dennis: During the lead up to the latest Iraq war and during the early stages of the war, I was looking a lot at historic Iraqi pots and thinking about the tremendous loss of the antiquities when the U.S. troops first went in and didn’t protect the museums. So I was thinking about both the loss of antiquities and the human loss. And I was doing this series of pieces that were based loosely on historical Middle Easter forms and that particular piece seemed to be a bomb canister form, so I thought about where Abraham was born and the thought that something of this sort may have been found unexploded as a bomb canister. It’s about the loss and the danger and the cost of this war. I wanted to have people look at it as something that could have been found.

T: It’s interesting for me to think about that piece alongside the work that my Christian Peacemaker Team colleagues did in that same time period documenting these large piles of unexploded ordinance that were just abandoned and not really disposed of. I remember hearing about a show that you did where at the opening, you began breaking the pieces one by one.

D: The Father Abraham piece was actually in that show.

T: But it remained unexploded?

D: Yes (laughs). At that show, in March 2004, I talked about my Mennonite tradition and non-resistant pacifism and that I feel that its important that when you see something happen you don’t agree with that you don’t just sit back, but that you speak out. So I was talking about the need to speak out and make it known how you feel.

Rather than simply observe how people understood what I was saying, I wanted to illustrate with an action so I reached down behind the sculpture stand and pulled out garbage bag and covered my piece with it I then took my hammer and smashed it in front of everyone. I then said, “Was that okay?” It was my piece, it didn’t belong to anyone else. I didn’t get a whole lot of reaction. So I got another bag and I walked over to another room (the show was in two rooms in the Lancaster Museum of Art). So people followed me into the other room and I put the bag on another piece. I was getting ready to raise my hammer against the second piece when my pastor, Barry Kreider, intervened and stood in between me and the piece.

I didn’t know what to do, because I didn’t expect that. I expected someone to say something. But Barry just stood there. And there was no way I was going to reach around the piece and smash it.

I just hugged Barry and said “You really understood. You saved my piece.” I didn’t go farther and say, “You placed yourself in danger by putting yourself between the agressor” or anything like that. That would have made the message a little clearer to the audience. My plan was to break at least three until I saw whether I got a reaction until someone would say, “Don’t do this.” The third piece I was going to break was “House of Prayer” which was a mosque looking form. I think most people understood. I hope they did.

T : This moves into performance art in some ways.

D: Yes, it’s probably the only time I’ve tried something like that. I’ve thought numerous times before this of doing something physical at an opening that would give a little more drama to the event. I’ve thought that just having the work covered and unveiled one by one may be a way of focusing the opening audience’s attention to each piece at a time.

Dennis Maust working in his studio. Photo by Tim Nafziger.

Dennis Maust working in his studio. Photo by Tim Nafziger.

D: Can you tell me more about the story behind the museum being concerned about you using a black garbage bag to cover the piece.

D: I talked to the musem director before hand and told her this is what I’m thinking of doing. And she said, I’m going to have to talk to the board about this. Because they had a performance piece a few years ago where something went wrong where a guy nearly accidentally hung himself. So they wanted to know everything ahead of time. So they were the ones who asked me to cover things with plastic and said I would use a clear garbage bag. They were concerned about the connection with Abu Graib.

T: And Why do you think they were so concerned about that connection?

D: I think they knew how conservative Lancaster is. I assumed they were more concerned with it being misunderstood and that using a normal garbage bag would have lent some unintended meaning to the thing. Maybe I was more timid than I should have been by just accepting that as their prerogative.

Second Wave Mennonite artist-hood

Tim: There’s Chaim Potek’s image of the artist always in tension with the religious community. And certainly there’s plenty of stories of Mennonite artists and writers struggling in the Mennonite church to be taken seriously or to have their work seen as valid. But when I hear you talking about your work, it sounds like you’ve largely felt comfortable with your identity as a Mennonite. Is that accurate?

D: While it took a while to think of myself as an artist, my home congregation, Park View Mennonite, Harrisonburg, Va., always gave me encouragement and seemed to validate most of what I did as an artist.

T: So in some ways you were a second generation artist, with the first generation doing the work of carving out space for it.

D: Yeah, my Dad, Earl Maust, was involved in issues of whether the piano or other instruments could be used in the music department at Eastern Mennonite Univeristy. The art department wasn’t developed until much later and I was one of the first art department majors. We really didn’t have issues like those from five or 10 years before.

Crazy Quilt and Patchwork

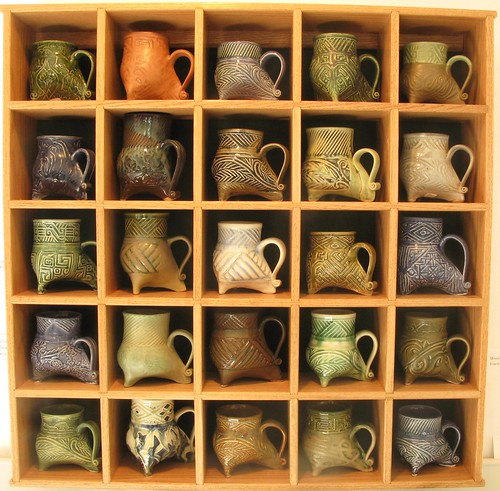

Three legged mugs by Dennis Maust

Three legged mugs by Dennis Maust

T: In your article, you use the image of patchwork and crazy quilt to describe your artistic vision. It strikes me that one of the artistic streams that has alwasy been accepted among Mennonites is quilting.

D: The piece I did that’s in the EMU campus center was certainly using the quilt as an acceptable art form and was a basis for that piece. It’s called Metamorphosis. But in the “Living the Patchwork” article, I’m really referring to the life I’ve lived here, which is a combination of various parts, not necessarily all related to my art. So yes, the quilt as an acceptable art form, was part of my understanding of something that was OK to do.

T: You also talk about this idea of different motifs from your travels and I got the sense of those coming together as a patchwork as well.

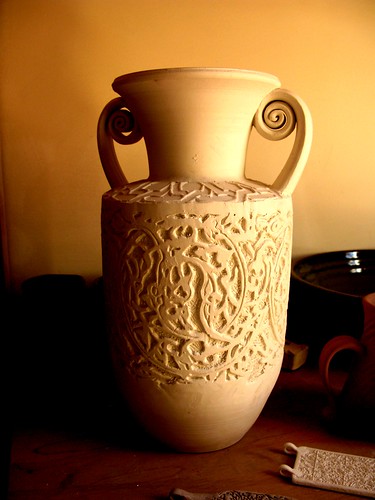

D: I do combine those in individual works. I use the motifs not in any kind of political commentary about the way they are put together, but I like that they are a part of my experiencec, varied though it may be. The fact that I’m putting motifs together from various parts of the world [see example in Untitled pot below] is simply an indication of the way our world is interconnected and because of contemporary communication our experience of multiple cultures is so much greater than it was.

T: It’s interesting that you define that you define that not as political commentery.

D: You’re saying its actually political commentary of another sort. Yeah, you’re probably right. But the way I use the various cultural motifs together is not intended to be a political statement. But maybe the fact that I do it that way is.

[We were joined by Rachel Hess, Dennis’s wife]

Rachel: So putting Africa with South America isn’t a political statement.

D: Yeah, so on that platter in there. It’s combining motifs from four corners of the world. Well, that could be a statement in itself. But its not a conscious statement in my mind. It’s not an overt thing. I haven’t named it in a way that would refer to it. I think it becomes political when I name it.

Rachel: I don’t think naming it is the only way it becomes political.

T: So the Father Abraham piece would be made very overtly political by its naming.

D: Yes, the name in that case confirmed the image I had.

T: I think this brings up some interesting questions about the act of creating art and both the unconscious and conscious acts of creating art. You talk about the importance of serendipity to you: enjoying the way an unexpected crack or break can enhance the art. How does your interaction with your audience impact your intentionality or consciousness about the layers of meaning? What’s it like when you have an audience who sees things that you didn’t intend?

D: It’s not very often that you find that out. I think at that opening where I did the dramatic action, I was concerned that my message might not be appreciated. The title of the Exhibit was “Messages” and I had some pieces that had Arabic calligraphy on them that were phrases from Hafiz’s poetry. He was from the Middle East and he wrote poetry that spoke to me. And so I had a friend write it out in Arabic script for me and I simply copied it unto the pieces. I wanted someone who read Arabic to understand some of my intent.

T: And so that would be another language that wouldn’t be for an English only speaker?

D: There were titles that alluded to the sentiment of the poetry. I think I had on the card a translation of the poetry. So for example, the piece “Friends Forever” and the line of poetry said in the womb we played footsy together. Before we were born we became friends. But it was to indicate how strong a tie we have regardless of circumstances.

If someone understands a work differently than I intended, I’m not worried about that. If they recieve something of meaning that relates to their understanding and their experience, I think that’s a good thing. I don’t feel like my work has ever been so misunderstood that its done some kind of harm.

T: You talked about in Tanzania being in the middle of a cultre that was post-colonial. Can you say more about what you observed and how that impacted your work?

D: It seemed a culture of mistrust existed, understandably, around foreign aid etc. Unfortunately that meant the organization we worked for rejected money and programs that would have allowed us to benefit more producer groups.

T: Can you say more about that work?

D: We were working with an organization call Amka (Swahili word for “wake up”) that was aiding small craft cooperatives and craft producing businesses.

T: So you would go around and talk with artisans and talk with them about how their work might be recived?

D: Yes, and how their work would be used and perceived.

T: So what’s next for you in the coming years?

D: I am hoping my work begins to merge my interest in pattern with more of my current Lancaster county visual vocabulary which includes my garden and the landscape of my life here as opposed to past life and travels to other parts of the world.

Bonus: My photos from last summer of Dennis’ firing his pots includes one of him working with a three legged mug and what appear to be parts of “Congregation” before firing.

Untitled Pot

Untitled Pot “Congregation”, 2012. Installation at Mennonite Church USA building in Elkhart. Photo by Dennis Maust

“Congregation”, 2012. Installation at Mennonite Church USA building in Elkhart. Photo by Dennis Maust