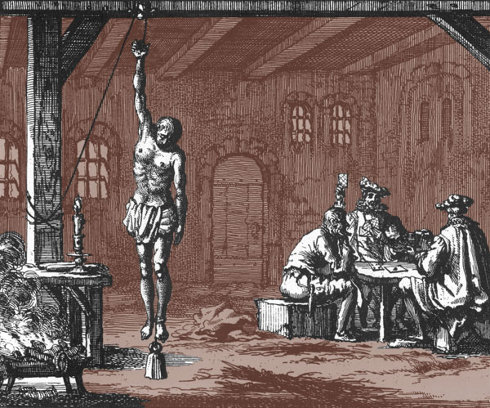

A page from the Martyr’s mirror depicting Geleyn Corneliss, who was hung by his thumb while his torturers played cards. Modified illustration from Third Way Cafe

Crossposted from As of Yet Untitled

Yesterday, March 6, 2013, we in the US learned in The Guardian that our government put torture and death at the center of our policy in Iraq. According to the article, Jim Steele, who was heavily involved in the El Salvadoran death squads, was called in to replicate the model in Iraq in 2004 with millions of dollars at his disposal. This strategy, known as the “Salvador Option” was apparently known and discussed at the highest levels of the US government and supervised closely by General David Petraeus. These actions are consistent with US policy since the end of World War II: torture and mass murder in support of US economic interests.

This is no aberration: it is the norm for empire. Nevertheless, many will hem and haw, rationalize and suggest this is still a few bad apples, albeit 4 star general apples. Tragically, most in the United States will simply ignore it. But what about us, as Mennonites: as Anabaptist Christians? What will we do?

Throughout our 400 year history, Mennonites have said no to war. But our “no” has been a passive, quiet one: over in the corner, tending our flocks and fields. We have not placed ourselves in the tradition of the Hebrew prophets with their unmistakable, angry indictment of injustice and violence in their community. We have often missed the connection between the stories in the Martyr’s Mirror and the ongoing torture of those outside our walls. Instead, the message we took was: resistance will be crushed. Redemption or not, our foremothers and fathers died horrible deaths. We were loath to follow and instead focused inward: protecting our own.

Gradually, over the last 50 years, Canadian and US Mennonites have been pulling our heads out of the sand. Our commitment to service put Mennonite Central Committee volunteers in contact with those most brutalized by US foreign policy. These volunteers have brought these stories with them to existing Mennonite organizations and structures, but they also helped to form new initiatives, like Christian Peacemaker Teams.

Yet the majority of Mennonites who voted in 2004 chose George W. Bush, mere months after the Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse broke. John Kerry would unlikely have been better and President Obama promoted General David Petraeus. However, that vote for Bush in that particular time and political space signaled a profound blindness on our parts to the same practices and patterns of this world that tortured and killed the early Anabaptists.

More recently I have anecdotal experience of this attitude. The Guardian clearly traces their investigation on these torture centers back to the release, by Wikileaks, of hundreds of thousands of diplomatic cables. In November 2010, On the day of that release, I wrote a post naming the tactics of Wikileaks as “cutting edge peacemaking” I said:

I believe the work they are doing is on the emerging edge of resistance to U.S. imperialism. The releases not only unmasks the powers in meticulous detail, but threaten the very mechanisms through which empire seek to influence, control and coerce.

Most of the comments in response focused on the personal ethics of theft and hypothetical lives put at risk by the leaks. There was a strong sense of “us” identified with the United States government and its policies and a remarkable unwillingness to discuss the unhypothetical deaths of Iraqi civilians and many others around the world by US empire.*

We, as Mennonites in the US and Canada, are unwilling to look systematically at the evil of our rulers, the authorities and “the cosmic powers of this present darkness.” (Ephesians 6:12, NRSV). Instead we focus only on the personal sins and our piety. The whole armor of God becomes a cutout for the felt board in Sunday school rather then a road map for resistance to the domination system.

Jesus’ whole life, death and resurrection was a witness against the project of empire and domination, both personal and social. We are inheritors to a tradition of dissent: of refusal to play by the rules of that game. If we let them, our faith can be our guide in challenging the colonization of our minds, our communities and our country by the principalities and powers. The same powers that set up the torture centers where Iraqis were beaten, shocked and raped in the name of our security and economic prosperity.

There was one hopeful note in this story. Neil Smith was the only US solider willing to go on camera to discuss US involvement in the torture centers and he did so because of his faith:

He now lives in Detroit and has become a born-again Christian. He spoke to the Guardian because he said he now considered it his religious duty to speak out about what he saw. “I don’t think folks back home in America had any idea what American soldiers were involved in over there, the torture and all kinds of stuff.”

I pray that these revelations today will wake us up as Smith woke up. Our slumber is destroying the dreams of millions.

P.S. For a related discussion of the ways that communities, including Mennonites, have responded to repression by creating redemptive narratives, see my comments at the end of the Iconocast interview with Noam Chomsky

*The most troubling response, because of its source, came from the editor of a mainstream Mennonite publication, identified publicly in his comment as “managinged” who also emailed me. He offered an article by Canadian Christian ethicist Margaret Sommerville. In an email to him, I pointed out that her arguments were from a Constantinian just war perspective that saw the US empire as a fundamental good and responded in detail to the way she so strongly identified with the apparatus of empire. He did not respond to any of my points, but instead asked me whether I would publish a leak from a Mennonite church institution – implicitly refusing to make a moral distinction between the institutions of the church and state. He concluded by asking whether Wikileaks wasn’t trying to “play God” by putting their hope in human judgement rather than trusting God as they should.

I am glad that someone is finally voicing what I have been thinking for so long. Our ‘pacifism’ while well founded in scripture, and was very active in Europe, here in America had evolved into ‘silence.’ Silence when others suffer, as long as it isn’t our own sons being asked to fight, we maintained our silence.

I am now looking thorough my family history. Many of those in my family who received draft cards, didn’t get called to fight, not because of their convictions, but because they were married, had children, and had farms.

Some however, were part of the militia in Northumberland county, formed to fend of ‘bloodthirsty’ Indians. The fact that Mennonites participated in displacing those who occupied these grounds in Pennsylvania, the fact that yes, before the American Revolution some Mennonites did pick up arms and join militias, is contrary to the mennonite-mythology I was fed at LMHS.

It is time to speak truth to power, in the tradition of our brothers and sisters in the uber-pacifistic organization Society of Friends.

Beautiful article. I’m not a Mennonite, but my beliefs are pretty much the same. For me, the question is “How should Christ followers address this issue?” :-)

Thanks for drawing my attention to this Guardian article, Tim. I in no way want to temper the excellent points you make, but I do have a concern with what could come across as false alternatives in your post, of which I’ll mention two:

“Throughout our 400 year history, Mennonites have said no to war. But our ‘no’ has been a passive, quiet one: over in the corner, tending our flocks and fields.”

I’m sure it isn’t your intention, but this statement can sound as though “tending our flocks and fields” and active resistance are in conflict. But, it seems that unless we have some positive vision of the peaceable kingdom, our anti-war and empire message will be a bit one-sided. I take it that this is part of the idea behind the new agrarian movement. Moreover, it’s painting with a pretty broad brush to describe–without any qualifications–400 years of Mennonites as passive!

“Instead we focus only on the personal sins and our piety. The whole armor of God becomes a cutout for the felt board in Sunday school rather then a road map for resistance to the domination system.”

Again, this reads to me like a false dichotomy: either personal piety (with its Sunday school lessons and all) OR political resistance. But, it seems that unless we are formed and habituated in the stories of Scripture (flannel graphs and all), we won’t even know how to read the “road map for resistance.” In other words, I wonder what the “born again” Neil Smith in the story would say about the importance of piety along with his “religious duty” to speak out.

Again, these observations don’t detract from your otherwise strong points. I just worry that, at times, the rhetoric of more politically active Mennonites can make it sound as though there is a necessary wedge between traditional Mennonite practices and active resistance.

Pingback: Week’s Links |

I would disagree with your comment: “Jesus’ whole life, death and resurrection was a witness against the project of empire and domination, both personal and social.”

However,, there’s no question that as Christians we should exemplify a peaceful life. Part of that may simply be tending our farms, but how do we speak and be heard? I think the best way to do that is to speak truth in a non-partisan manner. Our sides need not be with either Democrats or Republicans but be issue based. Our vocalizations need to say “We are not against Republicans or Democrats, we are against the constant warmongering of our culture.” When we single people out it cuts them off and numbs them to our message.

Marlene, can you share more about Mennonite involvement in Northumberland county militias? I was not aware of this and I’m particularly interested in that time and period because that’s when some of my ancestors arrived in Pennsylvania.

David, thanks for your observations. I strongly agree on the importance of the new agrarian movement for rooting our resistance. Ellen Davis’ observations on Nahala in Naboth’s vineyard have been influential for me in thinking about CPT’s work with small farmers in the community of Las Pavas. In my own journey as a Christian, the personal component of transformation and shared brokeness are linked up with social transformation. That’s why the crucial word only is in there. Two years ago I wrote about this more in depth in The Messy Meaning of Easter.

I, like you, worry. I feel cautious. Might I offend someone? I wonder if I should rein in more colorful turns of phrase. For me this is rooted in my upbringing in a Mennonite community. After all, it was only a few generations ago when humor was frowned upon by Mennonite bishops and fiction was “lies.” Then there’s the many other pressures to rock the boat as a child. As I said above, Mennonites have plenty of good reason to want to please people.

But then I spend a few days with the Las Pavas community in Colombia and I see the abuse they experience from corporations who embody the Washington Consensus. It is this same consensus that destroyed so many lives in El Salvador and Iraq. I come back to these lines from King’s letter from Birmingham jail:

I hear the voice of the farmer in Las Pavas who has had his trees destroyed and his cattle killed. And it’s more urgent than my concern at offending my traditional Mennonite cousins. I believe now, like then, is a time for catalyzing prophetic challenge to the domination system, silly similes and all.

TimB, I agree with you that we need to say, “we are against the constant warmongering of our culture.” Republicans and Demcrats are both part of that culture. They both support war.

You summed war up well in your comment over on The Mennonite:

Oh, and to prove my felt board cred, here’s what I’ve been carrying around to conferences for the last five years.