I originally published this review in with the Anabaptist Network in November of 2005 while working with them in London, England. I’ve been surprised how often the themes in this book have come back to me over the years and its one of the few books that made its way with me all the way from London to Chicago and then to Oak View.

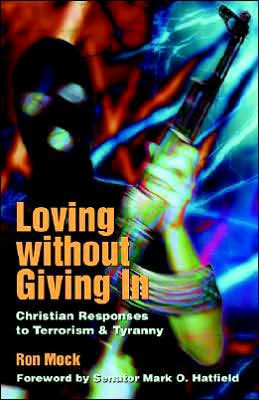

Loving without Giving in: Christian Responses to Terrorism and Tyranny

Ron Mock (Telford: Cascadia Publishing House, 2004) £14.50

In the wake of the 7 July bombings and the response of the British Government, Christians in the United Kingdom would do well to consider this book. Ron Mock begins by working through five aspects of terrorism: violence, lawlessness, political motivation, targeting of civilians and operation through fear. In each area he looks at examples of terrorism that fall within his criteria and case studies that do not.

Drawing on an idea similar to Walter Wink’s, he names the ‘the myth of effective violence’ — that violence against civilians is an effective tool for political and social change. As an example, he points to the birth of the Israeli state, which came about in part through terrorist attacks that he claims taught the myth of effective violence to Palestinians who now use these same tactics (p45). He goes on to differentiate the goals of terrorism from its methods, making the case that there is no cause that can justify lawless violence against civilians for political purposes.

Anabaptists and pacifists may disagree with Mock’s perspective on violence and government. He takes the Hobbesian view that the violence of the government is justified because it is the only thing that stands between us and anarchy. So the violence of the government stands on a higher moral ground than the violence of non-governmental groups and individuals.

Yet bad governments, according to Mock, are a cause of terrorism. He outlines three political systemic failures that are a spawning ground for terrorism: corruption, tyranny and anarchy. He calls for Christians to respond to the politically oppressed in the same way that we respond to those in material need.

Alongside state-related cuases, Mock also describes a spiritual dimension stemming from corrosive grievance. Grievances become corrose over time as injustice is unaddressesd and unheard. Gradually bitterness and despaire build up in a way that distorts people’s perceptions.

While Mock recognises the enormity of these systemic issues, the strength of the book is the way it empowers all of us to take small steps against terrorism at its roots. These steps are part of a broader framework based in Christianity and non-violent engagement. Mock identifies a triangle with issues, processes and relationships forming the three corners. He suggests specific responses in each area. Mock reminds us the roots of terror exist in all of us. For example, he identifies dehumanization as one of the roots of terrorism and goes on to confess the way he unthinkingly dehumanizes people in his daily life. ‘Dealing with people as things, or as mere members of pre-assigned categories, is a lot easier than recognizing them as people’, he says (p146).

Mock lays out biblical and secular arguments for responding to terrorism with non-violence. He points out (p170) that isolated enemies may drift even farther into extremism. ‘Too often we try to run off anyone who shows an inkling of befriending our foes because we focus on the risk that the enemy will thereby become stronger. But an enemy with friends working for peace is less dangerous, not more, because such an enemy has a powerful antidote to dehumanizing hatred.’

Above all else, Mock is very clear that we must never give in to terrorism. His suggestions are quite similar to many of the statements that have come out since the July 7 bombings in London: “We must refuse to be cowed. The more we stand up to fear, the less coercive power the predator has at his disposal.” He says. “This reduces the pay-offs he can expect from violence and makes it less likely that he or his cohorts will try something in the future.”

But Mock goes beyond simply asking us to return to our daily routine after terrorist attacks. He calls for Christians to actively go to places where terrorists operate and where civilians are targeted by terrorists and tyrannical regimes.

I have some concern with Mock’s analysis: he places a strong emphasis on ‘making decisions based on merits’ and includes free markets as an example. He sees them as an important way of responding to problems before they escalate into armed struggle or terrorism. But he almost completely ignores the growing international opposition to globalization which operates using the rhetoric of free markets and free trade. By advocating the free market without addressing the damage done as a tool of multinational corporations, he ignores its potential tyranny and oppression that has little do to with merits. In doing so, he loses touch with the grass roots perspective that makes his book so insightful.